TSPDT Rank #80

This is the first in a series of posts focusing on some of the 1,000 Greatest Films that I've seen but haven't been covered on my blog before. In the near future, I hope to start collecting these posts and the ones already on my blog into a comprehensive collections of 1,000 Greatest Films reviews. Stay tuned...

Initial viewing: c. 2007

For viewers who come to A Clockwork Orange without much knowledge of film history, seeing a masked hoodlum beating a man and raping his wife while tap dancing and gleefully singing “Singin’ in the Rain” might not feel quite as shocking as it does for someone who grew up watching Gene Kelly musicals on TV. For audiences in 1971, this was enough to send many running for the lobby and vomiting at the horror of what they had just seen. Seen by today’s standards, it’s clear that there is a lot of dark humor woven into this tale of a dystopian society overrun by amoral young thugs and unable to prevent its own moral deterioration. But even so, that infamous scene retains its sickening power.

Of course, this Stanley Kubrick masterpiece is more than just one scene. From its opening shot of Alex (Malcolm McDowell) staring into the camera with a chilling leer, slowly zooming out to reveal him and his mates sitting in a decadent futuristic bar decked out with naked porcelain women for tables and drinking milk laced with psychedelics, A Clockwork Orange casts a spell unlike any other. The dystopian world it depicts is both familiar and surreal, with bright colors and stylistized decor barely disguising the squalid, crime-ridden reality underneath. The film’s dazzling visuals draw the viewer helplessly into Alex’s world and often serve to make its sequences of violence as beautiful as they are disturbing.

I first saw A Clockwork Orange when I was in middle school. It was an illicit viewing - something that I wasn't supposed to be watching. But I was drawn to it as a fan of Stanley Kubrick's other films, like many young fans who talked their parents into taking them to the theater to see it back in 1971. Even though it was initially rated X, coming on heels of the huge commercial and critical success of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick's name gave it a prestige that set it above other "adult" films of the time. As for myself, what initially interested me about it was not the adult content, but the central psychological problem, and what it still has to say about our world today.

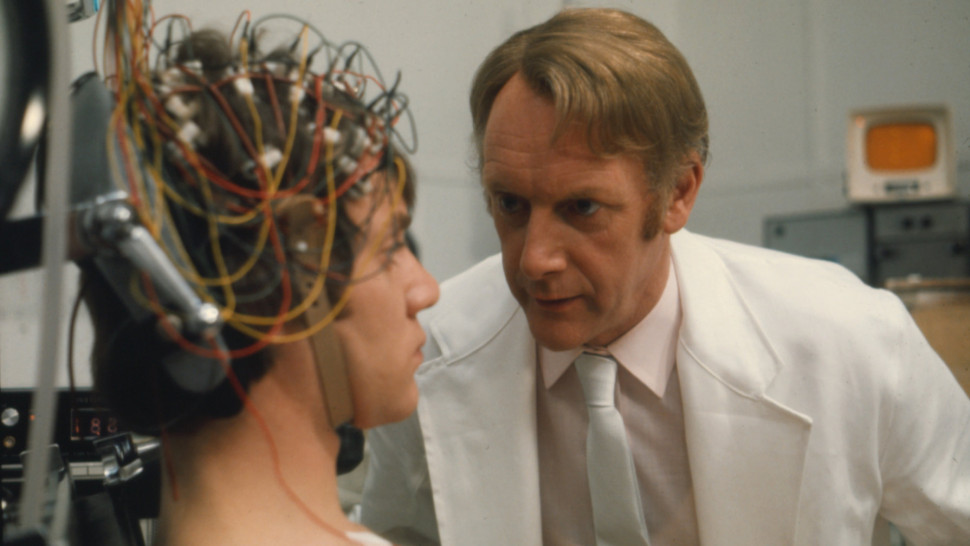

Alex’s psychopathic amorality is one of the film’s most fascinating points, owing to the magnetic performance of Malcolm McDowell. In Lindsay Anderson’s if…, McDowell brought a dangerous edge to his performance as a young rebel enamored with the idea of violence as a means for revolution. Here, McDowell uses that same edge to portray a character enamored with “ultraviolence” as a source of pleasure and dominance. Kubrick amplifies his performance with close-ups and low-angle shots, such as one key shot in which Alex wields a giant dildo sculpture as a weapon while standing over a cowering victim. At the same time, he subversively dares the audience to choose between Alex the charismatic psychotic or Alex the helpless test subject stripped of his freedom of choice.

Watching A Clockwork Orange today, it’s impossible not to wonder what it would have felt like to see it upon its original release in 1971. It’s as dangerous and deranged as its main character, with over-the-top performances, pompous dialogue filled with imagined futuristic slang, colors as lurid as its scenes of sex and violence, and a bombastic narrative style which marries perfectly with the music of Alex’s beloved Ludwig van Beethoven. It embraces Alex’s amoral worldview with disturbing faithfulness--eschewing moral commentary of any kind and casting all of its characters as ridiculous caricatures. Nevertheless, there are many universal truths to be found here about hypocrisy and the slippery nature of morality. It’s a disturbing, hilarious, bizarre and unforgettable satirical masterpiece.